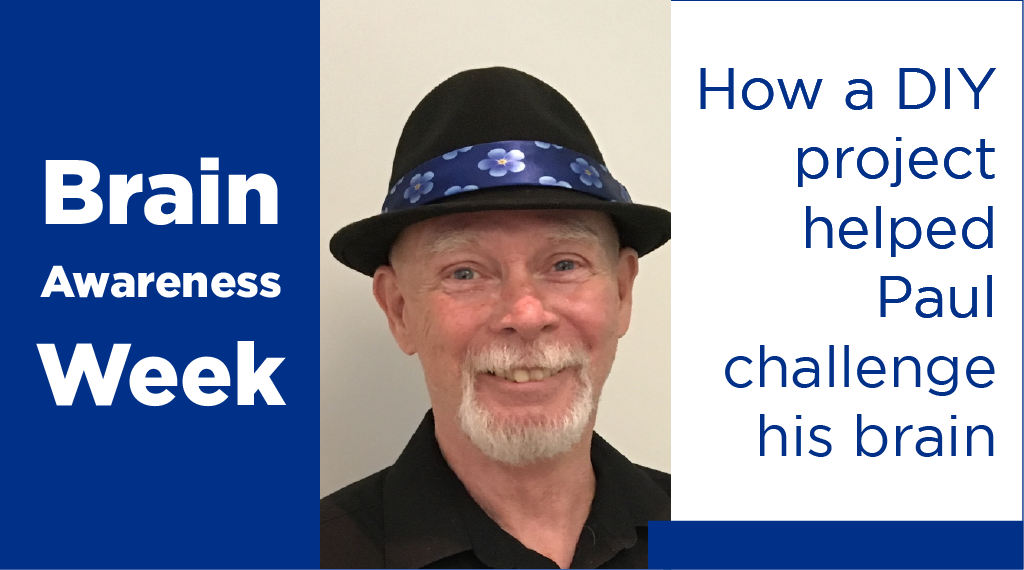

Brain Awareness Week: How a DIY project helped Paul challenge his brain

Paul Lea, who lives in Toronto, Ontario, was diagnosed with vascular dementia in 2009. But that didn’t stop him from seeking ways to stay mentally and physically active. Lifestyle changes are not only important if you are living with dementia but they also help reduce your risk of developing the disease.

By Paul Lea

Every morning, I say, “thank you” for being alive. It’s my way of keeping my perspective in check. Since my diagnosis, I’ve had to learn my limits, but I’ve also accomplished things that no one would have expected. Over the past decade, I’ve left my old life behind and come back with my new one, and the success of that new life is due in part to how I challenged my brain. This is my story.

The first signs

I enjoyed being at Levi Strauss. There, I was a quality control auditor, and I performed that job well. You could say that my biggest vice at that time was my smoking habit, but otherwise, I felt healthy.

However, in 2006, unusual things started to happen. I began to feel confused at times and would forget what I had just been doing. As an example, I found myself unable to fold a shirt back into its package after inspecting it. Sometimes I couldn’t feel my face, and my limbs would go limp, and this numbness would last for around 30 seconds. And every now and then I had what I can only describe as ‘kaleidoscope’ vision that lasted for minutes. I didn’t know it at the time, but these were all signs of a stroke.

After a difficult experience driving my daughter from work, she told me to go to the hospital. However, my family doctor stated that there was nothing wrong—and, further, that I was a hypochondriac. (Needless to say, he’s no longer my family doctor.)

Then, in the beginning of December 2008, it happened. I was walking to my car in a parking lot and started to lose vision in my left eye. I lost my peripheral vision, and I stumbled right into a parked car.

It was a strange experience, but at the time I thought that I only needed to get some glasses. But my optometrist suspected that the answer was more complicated than that, and referred me to a hospital in downtown Toronto. There, I was subjected to two young doctors arguing with each other over what I had, and neither bothered to include me in the discussion. It felt more like they were trying to one-up each other instead of helping me out. So, I gave a polite “thanks” and left them to their bickering.

The diagnosis

Later that month, it happened again. I lost vision in my left eye, and this time I had severe pain behind it as well. I felt weird, so I called 911. This time I went to St. Joseph’s and there I finally got my diagnosis from the doctor: I had a stroke.

When someone thinks of a stroke, they usually think of facial paralysis, etc. I didn’t have those symptoms, and I felt fine, so I asked if I could go home. I had no reason to think that anything was going to be wrong. But the doctors thought otherwise.

“You’ve had a massive stroke. You should be dead,” one doctor told me. They didn’t know exactly what caused it, so I was kept in the hospital. After a week without any problems and no conclusions, they let me go.

Soon, I was referred to a neurologist, who, after prescribing some medication for my blood pressure and cholesterol, referred me to a psychiatrist in turn. During a discussion I had with the psychiatrist, she mentioned something about me having dementia.

I asked her point-blank, “Why are you calling me demented?” Then she told me that I had vascular dementia, and that it was caused by my strokes—something that the neurologist failed to mention.

The apartment

After I was diagnosed, I saw my lawyer, got my will drawn up, and gave Power of Attorney to my daughter. No one told me to do this, even though I could hardly understand, read or write at the time.

See, I don’t like being told what I can’t do. Though I had this diagnosis hanging over me, I didn’t feel that I was sick and in need of help. For one thing, I knew that I could live independently, and wanted to prove that.

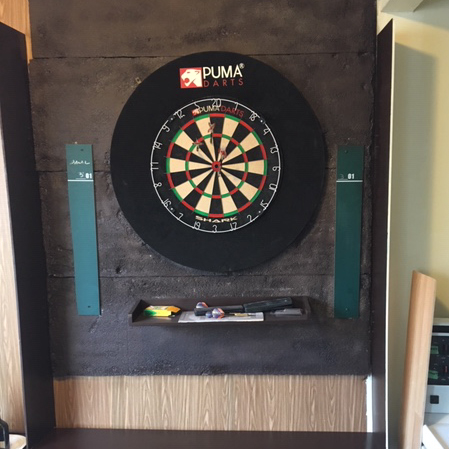

The apartment that I’d moved into was showing its years and then some—peeling walls and ceilings, a decaying kitchen, a broken medical cabinet…you get the idea. One door looked like it had been through a war, gutted and ripped. So, I decided to fix it all up. I used to be a handyman, after all!

I put trim around my bathroom floor and replaced some of the tiles. I painted the doorframes, too. Whenever I could, I’ll look for creative solutions to make my job easier—for instance, I’ll use spray paint instead of the regular brush. It was new to me, but easy for me to apply. Another example was when I wanted to put up a backsplash in my kitchen, but since they were too expensive, I used floor tiles instead. Counter-intuitive, sure, but it ended up working really well, with the tile matching the countertop, and it was cheaper. I always look for new pathways to fix a problem.

Whether it took me a month or a year, I’d get it done. The door that had been through hell and back took me six years to repair. But when I was done with it, that door looked like it had just come out of a factory. Fixing everything up made me feel good—this was something that I did, I did it by myself, and it ended up looking pretty nice!

Brain healthy living

Fixing up my apartment is just one example of how I challenged my brain. After I was told that I had dementia, I was given the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCa) test. Still reeling from my diagnosis, I only scored a nine out of a possible 30. But I later retook the test and got 15. Still not satisfied, I took it one more time and scored 28.

How did my scores improve? I made sure to work my brain. I play games such as word search and solitaire, and I speed-test them to give my brain more of a workout. I always find a way to challenge myself, I’m told by medical professionals that I’ve compensated well for the deficits that vascular dementia brings because I’ve worked my brain. I feel lucky in some sense—one doctor told me I belonged to a very small percentage of people with vascular dementia, as low as 1%, in terms of how I still use my brain.

I’m back to writing my own cheques again. I cook my own recipes; one of my favourites is a mince steak with stewed tomatoes and my very own spice mix.

My peripheral vision has improved as well. So much to the point that I’m even thinking of taking my driver’s licence again. When I was first diagnosed, one of my first thoughts was that I didn’t want to hurt anybody. So, I let my licence slide and sold my car. But now, I feel more confident in my abilities.

And my creative side is reflected in who I am today as an advocate for people with dementia. I took my fedora, and I took a necktie emblazoned with the Alzheimer Society’s Forget-Me-Not symbol, and I put them together to create a spiffy new hat…my signature look!

As for my smoking habit? I had smoked for 52 years, but it all stopped in 2014. Before then, I tried quitting many times, but it wasn’t until I knew that smoking could be linked to my diagnosis that I quit for good. At the time of my diagnosis, I didn’t know there was a relation between smoking and vascular dementia. Since then, I’ve learned that my heart caused my stroke, which caused my vascular dementia.

And I’m still working on my apartment—I want something else to do in my spare time at home, so right now I’m adding a dartboard. It’s not completed yet, but it will be! Whatever I start, I finish.

What have I learned as someone living well with dementia?

First, if you suspect something—anything—go to a doctor right away. And don’t be afraid to get a second opinion.

Second, don’t hesitate to get your friends and family involved. They will support you and may notice things that you don’t notice yourself.

If you’re in the medical community, you need to ensure that information is provided from the outset—when the diagnosis is made, you’ll be able to provide referrals, resources and recommendations for support groups. If I knew my vascular dementia was linked to smoking when I was diagnosed, I would have likely quit then, instead of five years later.

As well, make sure you’re including the person with dementia in the discussion, especially for a matter as important as a diagnosis. If they’re there with another family member, talk to both of them as equals.

Finally, I just want to say that there’s always a light at the end of the tunnel. It’s up to you how big or minuscule you make it.

Check out Paul’s work as a dementia advocate at Spare a Thought for Dementia.

Interested in learning more about giving your brain a workout? Visit the Alzheimer Society of Canada website.