“I am a person with dementia and a person with rights.” (part three)

Part three: Establishing human rights for Canadians with dementia

This blog series is based on the webinar, “I am a person with dementia and a person with rights,” hosted by brainXchange and presented by Phyllis Fehr on December 13, 2017 (part one) and January 17, 2018 (part two).

Previously in our series on human rights and dementia, we looked at how past experiences inspired Phyllis Fehr to advocate for dementia rights (Part one: Becoming a force for change—Phyllis Fehr’s story). Then, Phyllis showed us how seven articles in the United Nations’ Convention of Human Rights can improve the quality of life for Canadians living with dementia right now (Part two: Understanding dementia from a human rights’ perspective).

Today, in our final part, we’ll look at:

- a short history of human rights and dementia,

- how human rights and dementia are addressed in Canada,

- the current gap between human rights and dementia in Canada, and

- the next step in human rights for Canadians living with dementia.

A short history of human rights and dementia

This may come as a surprise, but you only need to travel back quite recently in human history—say, a bit more than 70 years—to find a world with no clear, agreed definition on what constitutes a human right. Today, we can safely define human rights as basic rights and freedoms that all people are entitled to regardless of nationality, sex, origin, race, religion, and language.

But, this definition didn’t exist until 1948, when the newly-founded U.N. adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. It was the first time in history that countries all around the world agreed on a comprehensive statement on inalienable human rights!

However, while the Declaration was important for introducing an international standard of human rights, what it didn’t do was protect the rights and dignity of those living with disabilities…like those of us who live with dementia.

It wasn’t until 60 years later that this gap was finally addressed, when the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (discussed in part two) came into effect in 2008. The Convention affirms that all persons with all types of disabilities, including people with dementia, can enjoy the full scope of human rights and fundamental freedoms—equal under law.

And yet, as a person with dementia, you may find that the Convention doesn’t always address your needs, either. After all, the Convention is very broad—while we can make use of the articles that Phyllis showed us, the Convention mainly applies to people living with disabilities in general. It just doesn’t focus on people with dementia.

Plus, since the Convention is international, it doesn’t necessarily reflect our unique Canadian values. As a Canadian living with dementia, what home-grown documents can you refer to for your rights?

How human rights and dementia are addressed in Canada

You can point to section 15 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which discusses equality rights. The Charter is Canada’s bill of rights that protects our right to “life, liberty and security of the person,” and this section enshrines the right to “equal protection and equal benefit of the law without discrimination.”

As well, the Charter sets out to protect those who face disadvantages in society by allowing for laws and programs that can improve their quality of life, like employment programs for people with disabilities, for example.

Also, as a person with a disability, you can look to the Canadian Human Rights Act to protect you from being discriminated against at your job or when you receive services. According to the Act, “all individuals should have an opportunity equal with other individuals to make for themselves the lives that they are able and wish to have and to have their needs accommodated.”

Three things that human rights can give to people with dementia:

- Protection. Human rights ensure justice and fairness within society and protect each person from discrimination.

- Vision. When human rights are codified, we can better identify who needs help. That lets us develop an agenda that can better accommodate their needs and drive change.

- Hope. They give us a moral vison of human nature and human dignity. What would life be like if everyone’s humanity and rights were respected?

The current gap between human rights and dementia in Canada

As a person with dementia, you may face stigma and discrimination every day. You may be challenged with attitudes towards your diagnosis, assumptions about your capabilities, and barriers in your physical environment (like lack of clear signage, for example). These obstacles can hinder you from participating fully in society.

We can help others understand dementia through public awareness, but we also need to ensure that the rights that protect people with dementia can be easily understood and accessed in a convenient manner. This way, we can ensure that people with dementia, like you, are included in the conversation about human rights.

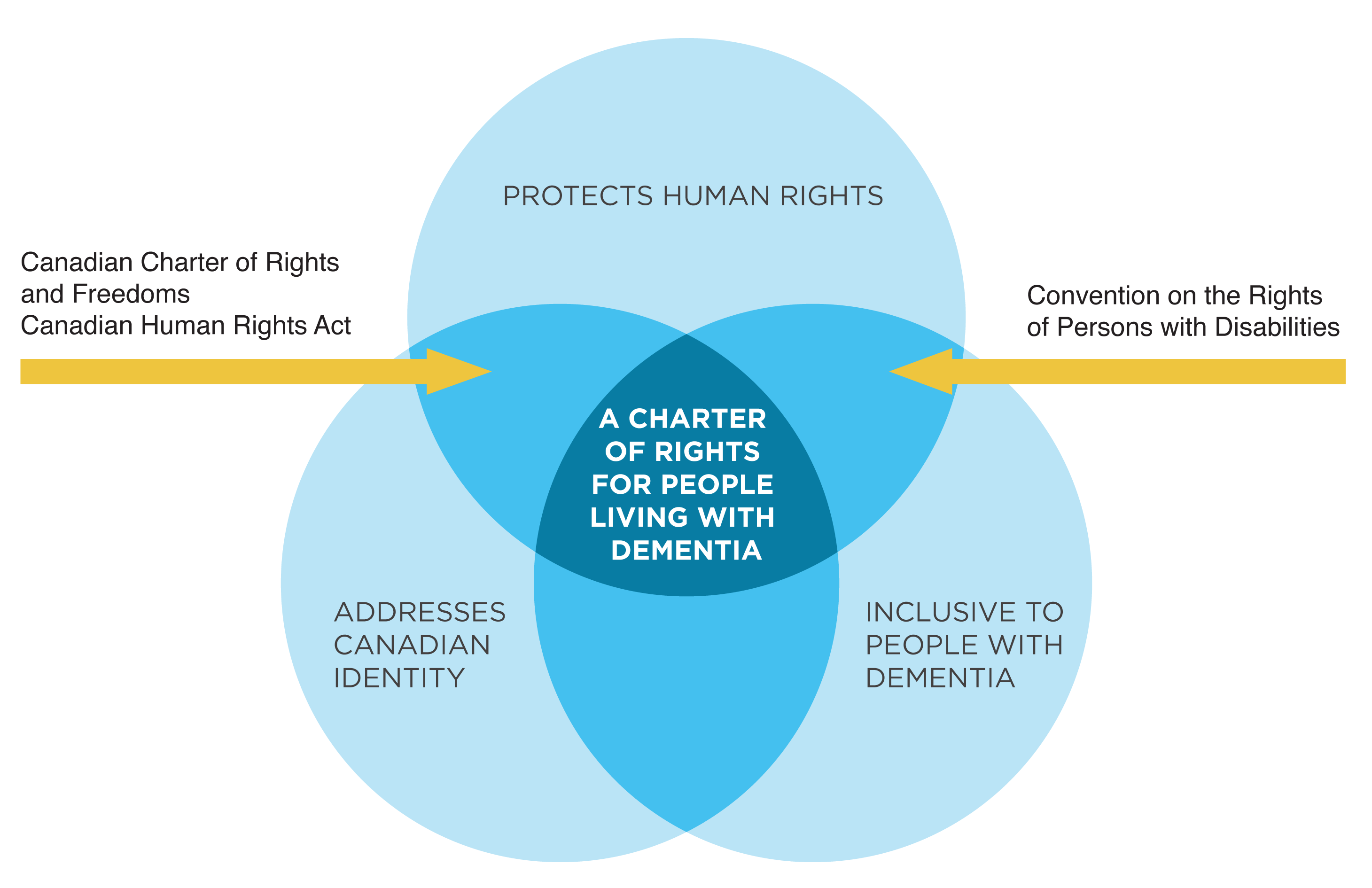

You may have noted that neither the Charter nor the Act addresses people with dementia. The closest the Charter gets is how it addresses people with cognitive impairment. Like the Convention, while these documents address the challenges that people with disabilities face, they may not be inclusive enough as references for people with dementia. It’s difficult to assert your rights as a person with dementia when our documents on human rights don’t explicitly name them.

But, from our short history of human rights around the world, we know that our thoughts on rights are always evolving. What we think and believe is true today may not necessarily hold true in five, ten, twenty years’ time. And as our thoughts on disability rights have evolved since the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was introduced, so can our thoughts on dementia rights also change within Canada.

The next step in human rights for Canadians living with dementia

So, how do we encourage change?

To start, we can look at how other groups living with disabilities address their rights. After all, each disability has its own challenges and stigmas. But when these groups start to stand up for themselves and fight for their rights? Change happens.

Take the Deaf community for example. Today, you can see sign language interpreters at conferences, events, even concerts; you can access closed captioning whether you’re catching a movie at the theatre or watching TV at home. These services weren’t always around though—it took plenty of hard work in awareness and advocacy to introduce Deaf culture and make these beneficial changes happen.

Secondly, organizations from around the world, from Scotland to Ireland to Australia, have already drafted their own charters and statements that have a rights-based approach to dementia. We can look to these to inform and guide us.

Finally, in Canada, we have a dementia strategy being developed nationally, and Alberta, British Columbia, Nova Scotia, Ontario and Quebec have strategies either already in place or in development that will improve the quality of life for people living with dementia and their caregivers. These strategies will empower you to stand up and say that the stigma and discrimination you face is unacceptable. By having rights solidified through these strategies, people with dementia can be included in the conversation.

Make no mistake—our own charter of rights is coming our way for people with dementia. In the near future, expect to see evolved documents that will address and protect your rights as a person with dementia. Through human rights, we will see change for the better.

If you are interested in learning more about human rights for people living with dementia, stay updated with the Alzheimer Society of Canada by following us on Facebook and Twitter for the latest news.