Life with young onset dementia: What you need to know

What comes to mind when you think of a person with dementia? If you’re like most people, you picture an elderly person in the later stages of the disease.

But here’s the thing: dementia doesn’t just happen to older people. While age is still the biggest risk factor, people in their 50s, 40s and even 30s can also develop dementia.

We call this young onset dementia and it accounts for about 2-8% of all dementia cases. Right now, 16,000 Canadians under the age of 65 have dementia. A dementia diagnosis is difficult for anyone, but it’s especially challenging for people in their 40s or 50s.

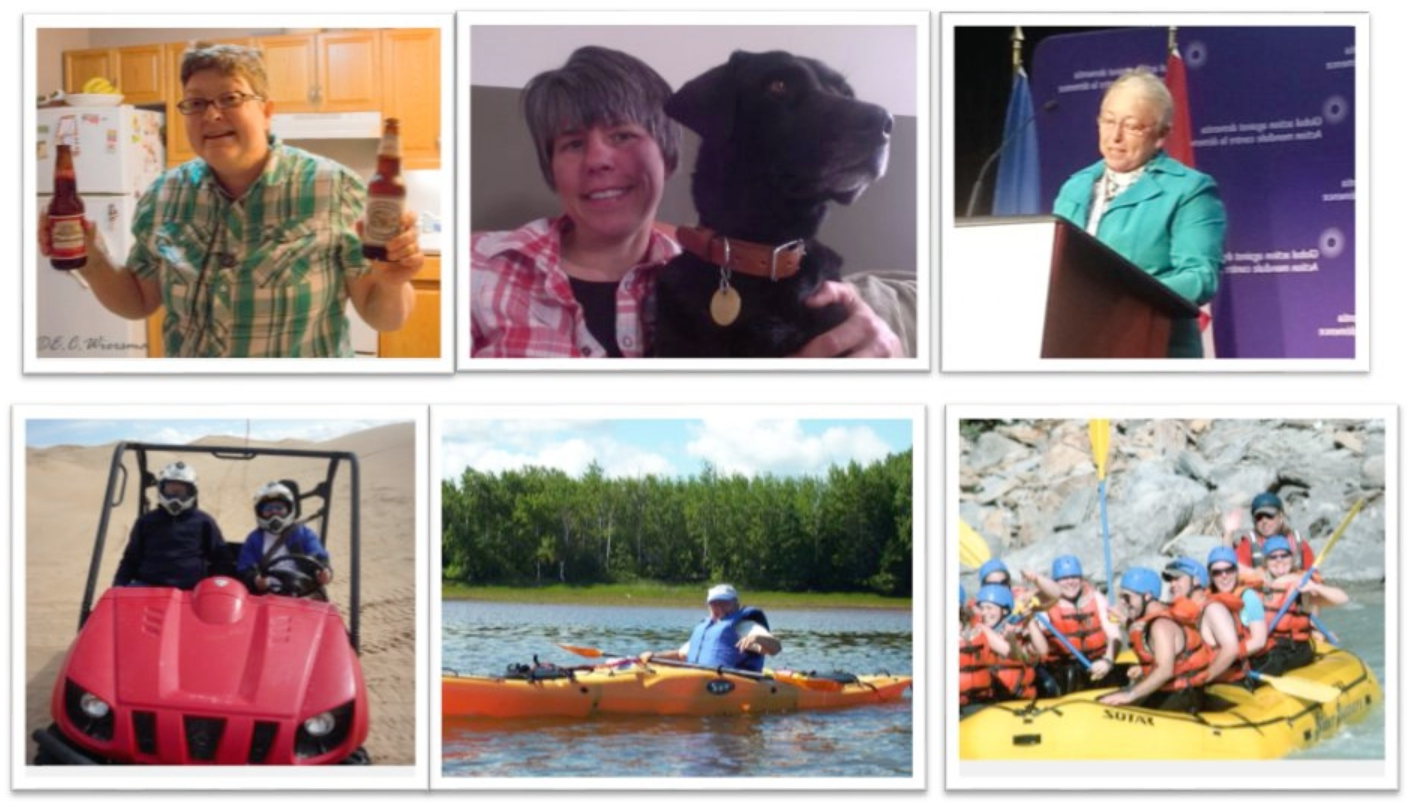

Faye Forbes (left) and Mary Beth Wighton (right) are both living with young onset dementia. Faye was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease at the age of 58 and Mary Beth was diagnosed with probable frontotemporal dementia at age 45.

That’s what we recently learned from Mary Beth Wighton and Faye Forbes, who shared their experiences of living with young onset dementia during a webinar co-hosted by the Alzheimer Society of Canada, brainXchange and the Canadian Consortium on Neurodegeneration in Aging (CCNA).

Here are some of the biggest takeaways:

It’s a long road to diagnosis…but it’s worth it in the end

Diagnosing dementia can be a long and complicated process. For younger people, it’s even more complicated and frustrating. Medical professionals are often reluctant to diagnose dementia in someone so young, and it’s common for people with young onset dementia to be misdiagnosed with other conditions. In fact, Mary Beth and Faye were both initially diagnosed with depression.

“(The challenge) with young onset is that dementia is not something that they think about initially. If you’re a woman, the first thing they think about is menopause and depression and anxiety and panic and sleep disorders and all those kinds of things.” – Faye Forbes

“I had 12 different diagnoses before being told that I had probable frontotemporal (dementia)…they included: PTSD, major depression, forgetfulness, no short-term memory impairment, OCD, panic attacks, conversion disorder (what that means is that it’s all made up in my head). I was told that I was over-reporting memory complaints, I had frontal lobe problems, I had a pituitary cyst, I had REM sleep behaviour disorder, and ultimately that then resulted in a diagnosis of probable frontotemporal dementia.” – Mary Beth Wighton

Still, both women felt that getting a diagnosis was well worth it in the end:

“Once you have that diagnosis, it’s something that you can grab onto. There’s something there that you can fight against. That’s the way I looked at it and I wasn’t going to let it get me down. I wasn’t going to just sit there and roll over and let things happen (…) And I still look at things like that today.” – Faye Forbes

“When I think about that diagnosis, in one way, it was a really good thing, because then I could move forward with my life…As challenging as that looked, we could do it.” – Mary Beth Wighton

It’s an uphill battle to overcome stigma…but supportive family and friends make all the difference

People with dementia often feel excluded or treated differently because of their condition. For younger people with dementia in particular, there’s a tendency for others to dismiss the condition as a mental illness, or to simply not believe it because of the perception that dementia is just a disease of the “old.”

“I had all those years of people telling me I was messed up and it was all in my head, and…it was very, very hard on my family, because they were being told by other people, ‘she’s lazy,’ and ‘why don’t you leave her,’ and ‘she’s just nothing but problems,’ and so thankfully my partner and my daughter resisted all that and recognized that it was truly an issue.” – Mary Beth Wighton

We know that many people with dementia go on to live very fulfilling lives for quite some time, but even health-care professionals seem to offer little hope or support for life after diagnosis:

“(The neurologist) just looked at me and said, ‘You have dementia. You have Alzheimer’s. In five years, you’ll be in a nursing home.’ It was not a positive experience at all.” – Faye Forbes

“(My partner Dawn) said, ‘Oh, this is great, we have a diagnosis, what do we do now? Is there a pill, or…?’ And this is when the doctor said: ‘No, there’s no pill, there’s nothing that we can do at all,’ and you’ll have to basically ‘go home, get your affairs in order because you will die from this.’” – Mary Beth Wighton

Mary Beth turned to the internet for more information. There too, stigma was prevalent:

“(After diagnosis) I got home and I started to do all this research…again, it was all the doom and gloom and stigma and, ‘You’re not going to be able to do this,’ and ‘I’d be sexually assaulting people’…these were the things that were coming at me.” – Mary Beth Wighton

In spite of these challenges, both women have embraced living positively with dementia, bashing stereotypes and misconceptions along the way:

“I had started going back to school and studying for ordained ministry prior to all my symptoms starting. And I continued that…I was bound determined that I was going to achieve that goal regardless. And I did…I’m part of a team ministry in my parish and I love doing it.” – Faye Forbes

“I’m a fighter and I’m very stubborn… I just thought, ‘No, I can get around this, I can beat this, I can do something.’… (So) I started doing a lot of advocacy work. Over the last two years in particular, I’ve seen the ability of what happens when people (living with dementia) who are empowered as individuals join forces (…) to push things like policy forward.” – Mary Beth Wighton

[As part of her advocacy efforts, Mary Beth co-founded the Ontario Dementia Advisory Group (ODAG), a group composed of people living with dementia who work to influence policies, practices and people on issues that affect their lives. Learn more about ODAG at odag.ca.]

There’s a huge gap in services and supports

“I unfortunately ran into that brick wall where I was ineligible for just about everything because of my age.” – Faye Forbes

People with young onset dementia are often still working at the time of diagnosis, are physically fit, and may have dependent children or parents at home. They likely have major financial commitments like a mortgage or student loan. Yet, most social programs and services are designed for older people with dementia. They may not be of interest or the person may not feel comfortable in a seniors’ program. They might even be ineligible to join because of their age!

“I ran into a problem getting in to see the gerontologist because I wasn’t old enough to be part of the geriatric clinic.” – Faye Forbes

“I was too young to join (programs) because I was still in my 40s.” – Mary Beth Wighton

Faye and Mary Beth also describe the lack of a supportive health-care team.

“We know when someone gets a diagnosis for a different disease, like cancer, (…) a team of support will surround that person, like for instance a dietician, oncologist, spiritual advisor, financial advisor, etc. What happens when you get diagnosed with dementia in Canada? That does NOT happen. We are unlike any disease. We, for the most part, are literally told to just go home and die.” – Mary Beth Wighton

But there are many services that could be helpful for a person with young onset dementia that one might not even consider.

“One of the things that is important for a person with dementia is our diet (…) And yet I don’t know anyone (with dementia) who has access to a dietitian. That’s not part of our diagnosis process (…) Other things are occupational therapists (to help adapt your home to changing abilities) (…) Physiotherapist, for instance, is really important. People begin to, depending on the type of dementia, it could be more of a struggle for them to walk or to speak or to find those words. How come we don’t have a speech pathologist with us?” – Mary Beth Wighton

And let’s not forget about the family members.

“For my family, there wasn’t a lot of support. Through the Alzheimer Society my partner does have a social worker, but other than that, nothing.” – Mary Beth Wighton

Many are forced to give up working in their prime earning years

Many people with young onset dementia are still working when they’re diagnosed. Some may be able to continue working by modifying their job. Others will have to stop working immediately, which comes with major financial, social and psychological implications.

“At the age of 45, most people are looking to be at the top of their career or starting to head at the top of their career and get into that high income earning, and for me I had to take a long-term leave from my employment, and that then turned into having to leave my job.” – Mary Beth Wighton

“(At work) I really enjoyed interacting with people…I worked in a large office so I was constantly with people all day long. To stop that left a big void in my life.” – Faye Forbes

It’s a major financial blow

The financial repercussions of living with young onset dementia are very difficult. Eventually, a person has quit their job and may not be eligible for financial supports.

“There was definitely a drastic cut in our finances, I was fortunate to have private disability that we (still) get today, and I also get CPP as well…I applied for Canada Pension Plan even though I’m only 50 years old.” – Mary Beth Wighton

For Faye, being a stay-at-home mom made things especially hard:

“I was a stay-at-home mom for most of the years that my children were growing up, and when I did go back to work and then had to leave work, it was about three and a half years that I had worked, and when I applied for Canada Pension, in black and white, in the very fine, fine print, it says you have to work four out of the last six years. So I was ineligible for anything like that.” – Faye Forbes

Living on a disability pension can cut a person’s earning capacity forcing a person to make some tough decisions. Both Mary Beth and Faye had to sell their family homes.

“You start to make decisions…so we made decisions, for instance where we lived, so we decided to sell our house, we just started to think differently…‘how can we live without the stress of finances’. And so we were luckily able to do that and I think we’re in good shape. But, you know, it definitely hasn’t been easy.” – Mary Beth Wighton

Additional expenses like drug costs and fees for support services also come into play.

“When we’re talking about other support services like dieticians, physiotherapists, psychologists, social workers…depending on how (well) your health care system in your particular province is working…you might have to pay for those services. (But) because you’re on a financial restraint to start with, you can’t afford that.” – Faye Forbes

Fortunately, both Faye and Mary Beth have learned to overcome these challenges and live full lives with dementia. They offer the following advice for anyone diagnosed with young onset dementia:

- Connect with your local Alzheimer Society.

- Explore all of your financial support options. Talk to a financial advisor to find out what these are and how best to extend those options over a long period of time.

- Consult a lawyer to get your legal affairs in order. How do you want to be cared for when you can’t care for yourself? What are your wishes? Set up Powers of Attorney so that financial and personal care decisions are made by someone that you trust when you’re no longer able to make them yourself.

- Find out about work and government benefits.

- Explore local, provincial, federal and online support programs.

“Just know that if you do have a diagnosis of dementia, you can live well. You can do it. That’s the main message.” – Mary Beth Wighton

Above: Faye Forbes, Lori Michaud (webinar contributor), Roxanne Varey (webinar contributor) and Mary Beth Wighton are living life to the fullest with their families, despite all being diagnosed with young onset dementia.

For more information, please see our page on Young onset dementia.

P.S.: If you have the time, we strongly encourage you to listen to the webinar and hear what Faye and Mary Beth have to say firsthand.